Pancreatic Tumors Plan Their Travels

Researchers uncover an intriguing characteristic of pancreatic cancer that could detect – and potentially target – metastasis earlier.

Even as they develop at their primary site, pancreatic cancer cells are already expressing the genes that will determine where they will metastasize, according to new findings from Columbia researchers. The work, published in Nature Genetics, reveals a new facet of cancer metastasis, and points toward novel strategies for anticipating and blocking this deadly phenomenon.

The project began a decade ago, when Gulam Manji, MD, PhD, co-leader of the Precision Oncology and Systems Biology research program at the Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer (HICCC), was struck by the dramatic differences in prognoses for pancreatic cancer patients. People whose tumors metastasized to their lungs alone did far better than those with liver metastases.

“It was very gratifying to see patients with lung only metastasis doing very well, yet at the same time really frustrating as an investigator, because there was biology within them that we didn’t really understand,” says Manji.

Clearing the hurdles

Columbia maintains a large repository of tumor specimens, but the experiment Manji had in mind required detailed clinical annotation of each sample. Enlisting the aid of collaborators, students, and postdocs, he had his team sift through several hundred cases, eventually finding 131 patients with isolated metastases of pancreatic tumors to either lung or liver.

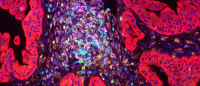

The next challenge was analyzing the tumor specimens, which often contain mixed populations of cancer cells and normal cells of the immune system and adjacent tissues. To study them, the researchers developed new methods for single-nucleus RNA sequencing and whole genome sequencing, obtaining detailed data on individual cells’ gene expression patterns. Benjamin Izar, MD, PhD, member of the HICCC’s Tumor Biology and Microenvironment research program, led the computational biology side of the project, extracting and validating findings from the deluge of sequencing data.

Language lessons for prospective visitors

Using a suite of new technical and analytical advances, and by integrating several other data sets, Izar’s group stumbled over an interesting observation.

“Cancer cells from patient’s primary tumours that ended up relapsing in the liver or the lung early on adopt cellular states that resemble their ultimate target organ. In other words, they already spoke the right language to ultimately fit in into their future organ community,” says Izar.

Even at their primary site in the pancreas, the tumor cells are already impersonating cells of their destination organ, predisposing them to survive there. A key question was whether a specific change in the DNA caused this observation. The researchers applied machine-learning approaches and studied additional large patient data bases to try to find an answer.

“We could not identify a single genetic event that could explain tropism to either liver or lung. While we have to remain open to alternative explanations, so far, we could not find a genetic reason for this intriguing result,” Izar says.

The researchers also looked at cultured cells from other types of cancers and found conserved signatures suggesting the same sort of metastatic foresight. “The key question now is what is the switch that takes these cells through these different programs?” says Manji.

While stressing that the results still need to be validated by other researchers and on more samples, Manji is excited about the effect they could have on patient care. In the near future, he hopes physicians will be able to refine surveillance strategies by predicting where a tumor is likely to metastasize. Looking further ahead, the gene expression profiles may point toward novel drug targets.

“Within the predictive signatures are likely embedded, determinants that allow these tumors to successfully establish a metastatic niche. Disrupting these key determinants is the next challenge which will likely produce a personalized drug for liver metastasis,” says Manji.

References

Additional Information

This paper, "Cellular states associated with metastatic organotropism and survival in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma," was published on October 27, 2025 in Nature Genetics.

Funding

Gulam A Manji is supported by NIH grants 1U01CA274312 and R01CA266558.

Benjamin Izar is supported by National Institute of Health grants R37CA258829, R01CA280414, R01CA266446 and U54CA274506; Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center Pilot Grants; the Pershing Square Sohn Cancer Research Alliance Award; the Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award for Medical Scientists; a Tara Miller Melanoma Research Alliance Young Investigator Award; the Louis V. Gerstner, Jr. Scholars Program; and the V Foundation Scholars Award. B.I. is a CRI Lloyd J. Old STAR (CRI5579).

This study was supported by resources of the Human Immune Monitoring Core (HIMC), Molecular Pathology Shared Resource (MPSR) and Cancer Biostatistics Shared Resource (CBSR) at CUIMC, which are supported by the NCI CCSG grant P30CA013696 and the Human Tissue Immunology and Immunotherapy Initiative.